In a post-pandemic world, is it still important or necessary for major metro areas to have a vibrant downtown at their core? If restaurants, retail outlets and housing are growing in Cherry Creek and other neighborhoods, does it matter if they’re on the wane or not as plentiful in downtown Denver?

Should efforts be made to fill or repurpose buildings that abruptly emptied out when COVID-19 hit and remain underused due to changes in work routines?

READ THE FULL PROJECT: At a crossroads: Downtown Denver is waiting for its rebound

Business and civic leaders say “Yes” to all of the above.

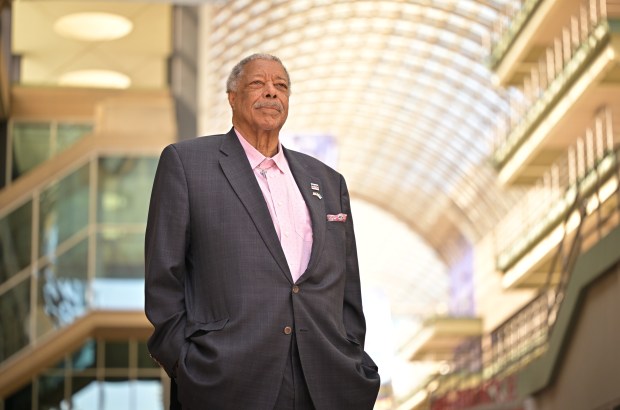

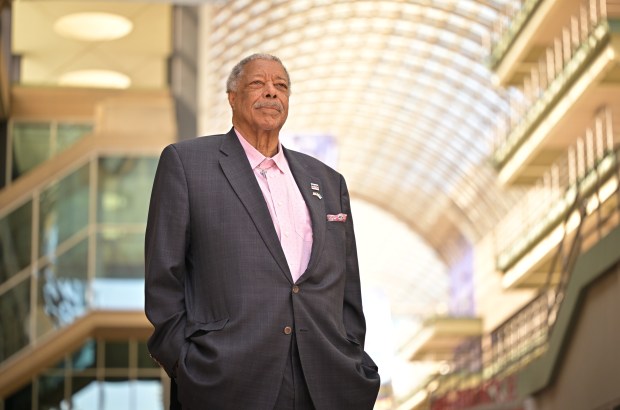

• “Downtowns are a living room for your city. That’s where you’re supposed to have people when they come in,” said former Denver Mayor Wellington Webb.”

• “I believe that downtowns, especially Denver’s downtown, are the heart and soul of metro communities,” said Federico Peña, who preceded Webb as mayor.

• “As a former economic development person, I can tell you that having a vibrant and central core to a metro region is important in the long run if you’re going to build an economy that can serve multiple industries and be resilient through ups and downs,” said J.J. Ament, president and CEO of the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce.

• “We’re 1.8% of the city’s overall land mass and pre-pandemic downtown represented about 13% of the city and county of Denver’s property and sales tax revenue. Today, we now generally represent only 8%. That equates to a decrease in the city’s revenue of $45 million annually,” said Kourtney Garrett, president and CEO of the Downtown Denver Partnership. Deciding whether having a robust downtown is still important, “in whatever form downtown takes moving forward, I’d say it’s pretty important,” Garrett said.

As in Denver, cities across the country are wrestling with how to restore the pre-pandemic hustle and bustle to recharge what has historically been a crucial economic engine. Approaches range from renovating or repurposing older, semi-vacant office buildings; boosting residential construction; and aiding small businesses.

While Denver leaders don’t think revitalizing downtown is a mission impossible, they say hurdles exist: fears about safety; tough-to-meet building codes; zoning restrictions; a bogged-down permitting process; and hybrid work schedules that keep office buildings semi-vacant.

“It does seem like we sometimes have one foot on the gas and one foot on the brake at the same time,” Ament said.

In the vast majority of downtowns in major metro areas, “I would would think that basically no one is at their pre-pandemic level of foot traffic,” said Tracy Hadden Loh, a fellow at the Brookings Institution whose areas of expertise include commercial real estate. She called the post-pandemic recoveries of downtowns a mixed bag.

One factor could be a trend that was evident before work and commerce were largely halted by COVID in March 2020. Loh said downtown areas were experiencing a decrease in the use of office space because of “telework Fridays” and companies cutting expenses by shrinking their footprint.

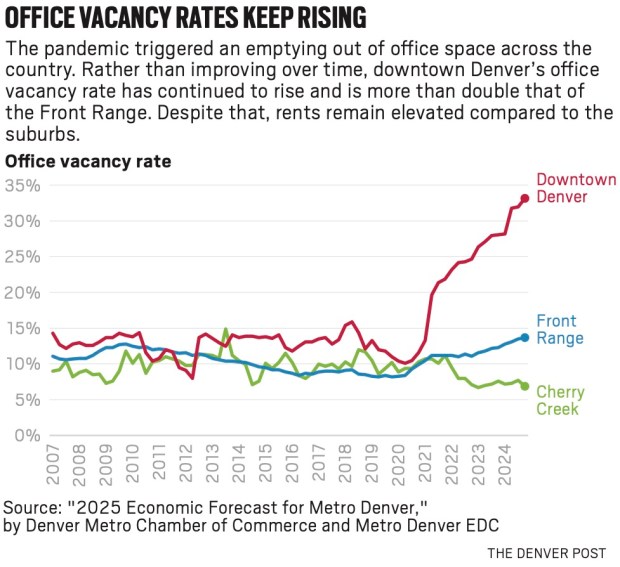

Downtown’s overall office vacancy rate is roughly 35%, believed to be the highest rate on record for the city.

As to how urgent the problem is, Loh said Denver’s office vacancy rate is high “even relative to other downtowns that are not doing well.”

Before the pandemic, downtown Denver had “a much bigger share” of the region’s overall job footprint — 13.1% — than in many places, Loh said. In the city, the downtown accounts for 30% of the jobs, according to a new report by the Downtown Denver Partnership.

A concentration of jobs that supports businesses and produces high tax revenue relative to the real estate they occupy makes downtowns “extremely important to their regional economies,” according to a 2023 research piece cowritten by Loh.

But rejuvenating the city’s core post-pandemic doesn’t mean business as usual. Loh co-wrote an earlier piece stressing the need for downtowns to evolve by modernizing offices, diversifying the mix of land uses and focusing on livability through public spaces, arts and safety.

Are downtowns still important?

For Rodney Milton, the question isn’t whether downtowns are still important. The conversation is more about the future of downtowns and the wisdom of building the core of a city around a central business district.

“It’s really the idea that you could have a single-use zone. Was that ever a good idea and if it isn’t, then how do cities that have chosen that path transform themselves?” asked Milton, executive director of the Urban Land Institute in Colorado and a city planner by trade.

ULI Colorado, one of the research and education organization’s largest district councils, is focused on the revitalization of Denver’s downtown and is working with business and other civic leaders. It’s a matter of taking what is the city’s most dense, compact and walkable area and reimagining it as a diverse neighborhood with a mix of uses rather than mainly a central business district, Milton said.

“What is the best way to go about doing that? You want to increase residents, so there’s your housing conversation,” Milton said. “You have to have the capacity to deliver a diverse type of housing.”

Cities where the downtowns were more focused on residents and varied uses rather than primarily centered on offices are the ones that are thriving, or at least haven’t been hit as hard economically, Milton said.

And while vibrant, multi-use areas that have developed in other parts of Denver and the metro area are important, Milton said, “… they’re not even remotely comparable to the economic engine that is downtown.”

The Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce is “politically and geographically agnostic,” Ament said. ‘We’re just as delighted to help something come to downtown Denver as we would be to Aurora or Lakewood or Lone Tree or any of the communities we serve.”

But no matter where companies might locate, they care about downtown Denver, Ament said. The state of what is a center for higher education, sports, entertainment and leisure matters to them because employers want to recruit and retain talented workers and employees “want to have the amenities that come with a vibrant urban core.”

Glenn Furton, an assistant economics professor at Metropolitan State University of Denver, believes it’s important to have a robust city center with high density to allow for a lot of mobility in the labor market.

“Not just labor mobility in terms of being able to pick up and move, but being able to choose a new job or dip into a new labor pool if you’re a business without having to move. That’s the benefit of a city,” Furton said.

Gotta get the swag back

Peña, who was mayor of Denver from 1983-91, is a fan of reviving the horse patrol downtown. He believes officers on horseback will provide an extra sense of safety following problems that came up after the pandemic emptied out large portions of the area.

“And it brings fun and entertainment to visitors. They love the horse patrol,” said Peña, a senior adviser to the Colorado Impact Fund.

A horse patrol is also a big nod to the city’s heritage, said Webb, who was mayor from 1991-2003.

“We have to appreciate our Western heritage and our new Western culture. We have to have a blend and a mix of both,” said Webb, founder and president of Webb Group International.

Peña and Webb ran the city during good and tough times. Peña took office as the economy in the middle part of the country started to sour. A bust in the oil and gas industry shook Denver and much of the Rocky Mountain region hard in the early 1980s.

“The first year in office I had to cut the budget,” Peña said. “I took 10 days of leave without pay and my fellow workers took five days leave without pay.”

Hours were cut at city recreation centers. There were a record number of foreclosures and bankruptcies.

“In Denver, after a year or two, our office vacancy rate was 30%. We were tied with Houston,” Peña said. “There was one year when the architects disappeared from Denver. They moved to Los Angeles. There was no business here. Downtown was hit hard.”

The city’s recovery strategy included building a new convention center downtown and making other investments through the Denver Urban Renewable Authority.

“We moved Elitch’s from north Denver into the current location. That spurred development,” Peña said. “We worked with the chamber (of commerce), with the Downtown Denver Partnership. We did a whole new downtown area plan. And slowly we made progress.”

City and business leaders are close to finishing a new downtown area plan. In a public meeting on May 21 to discuss the plan, project leaders identified seven major areas for development and investment, which include Denver’s Civic Center, Skyline Park, Upper Downtown, Upper Broadway/Arapahoe Square, the Cherry Creek/Speer Corridor, Central Platte Valley and the Ballpark/Sakura Square. Improvements could include expanding green spaces, creating pedestrian corridors, developing housing on underdeveloped sites, redesigning streets and activating the ground-levels of publicly-owned buildings.

That plan, along with the Denver Downtown Development Authority, approved by voters in November to issue $570 million in bonds, are intended to help rejuvenate the city’s core.

As Kroenke Sports and Entertainment builds its multi-use development around Ball Arena across Speer Boulevard from LoDo, it will be crucial to connect the site to the rest of downtown, Peña said.

“That development can enhance downtown. Downtown will be enriched,” Peña said.

But if the new development isn’t connected to LoDo,”that will become the new downtown,” he said.

KSE, owner of the Denver Nuggets and Colorado Avalanche, has filed a concept plan with the city that shows a two-branched pedestrian and bicycle bridge over Speer that would connect the development to LoDo.

Peña and Webb oversaw projects that helped catapult the city out of the economic doldrums: construction of Denver International Airport; landing Major League Baseball and National Hockey League teams; and the construction downtown of the Coors Field baseball stadium and Ball Arena, home of the Denver Nuggets and Colorado Avalanche.

The Denver Performing Arts Complex, down the street from the convention center, is the country’s second-largest arts center at 2.4 million square feet on 12 acres. Touring Broadway shows, the Colorado Symphony, Colorado Ballet and Opera Colorado are all featured at the complex, which has 10 performance spaces.

“People are coming from all over the region to come to the (arts complex),” Peña said.

The total attendance at the arts complex was 941,203 in 2019. During the pandemic, the numbers plummeted but rebounded quickly, reaching 890,150 in 2024.

More people working from the office every day would give downtown a charge, Webb and Peña each said. But they don’t expect the numbers to return to pre-pandemic levels. The return-to-office rate for downtown averaged roughly 60% in 2023 and 2024, according to the Denver Downtown Partnership.

Webb wants to see Denver build on the city’s major assets, such as the arts and sports attractions, to help spark a resurgence.

And there’s the power of swagger.

“The way I tried to sell it, in the ’90s early on, was, ‘Denver is the biggest, baddest thing going,’” Webb said. “We need to get back to walking with swag when we go to other places.”

Denver Post reporter Jessica Alvarado Gamez contributed to this report.

Get more business news by signing up for our Economy Now newsletter.

Leave a Reply